Hi there and welcome to Brandspace, a new minimal multi-purpose WordPress Theme from Pixelentity. As with all of our themes, Brandspace is speedy, lightweight and bursting with the latest tech.

HYPER-MERITOCRACY AND ARCHITECTURE

Excerpt from the lecture held at Architecture in Play international conference 2016

ISCTE-IUL university – Lisbon

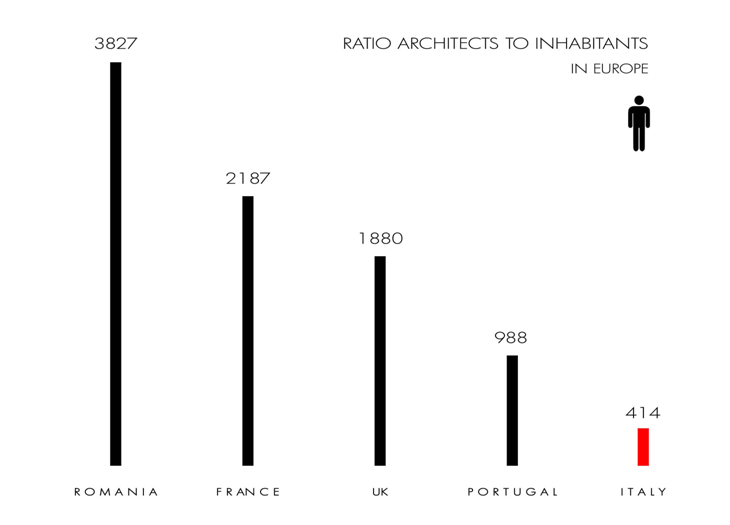

It is estimated that approximately 560.000 individuals in Europe are architects. The 35% of them is under 40 and the 74% of practices are one-person offices which work in measure of 55% in private housing. The average earning is about 30.000€ before-tax, but such a value is much higher for a minority and slimmer for a vast majority of architects. In Italy the 30% of under 40 declares less than 8.000€ per year. In a world where “winners take all”, big companies and archistars represent a small minority of highly competitive players, dominating the architecture market/business where relevant innovations and technologies can be applied. Conversely, the majority of architects work in a traditional, stagnant and loosely regulated market, often forced in offering low-priced services. They also suffering the competition of non-professionals (mostly in the interior design field) and this demonstrates that traditional skills are useless in a framework where any selective advantage doesn’t arise from merit.

Such a state of the art is the consequence of several conditions: unequal market, disproportionate architects supply, contraction of economy and, so far, lack of real innovation in the building process. Moreover, the economic crisis faced by western countries in the last years has brought to a considerable decrease of the spending power of people who consequently decided to reduce the expenses for unnecessary professional. The described landscape has generated a situation in which international firms have the interest and the economic possibility to be up-to-date in terms of information technology and building techniques whereas small firms or individual practices run the risk to be cut out from the market. If this trend were to continue, we could face an extinction of architecture profession as we know it, though human beings will continue to build houses and buildings.

The hyper-meritocracy paradigm

In his controversial book “The average is over” Tyler Cowen argues that modern world is on the cusp of a sea change, brought on largely by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI). That machine intelligence will kill most middle-class jobs, as well as the broad prosperity that has characterised advanced economies since the ’50s. In this sort of social Darwinism the survivors will be those whose skills complement those of the new technologies. One side effect of the rise of automation is that everything we do can will become measurable. In other words, winners will prevail through a process of “hyper-meritocracy” based on measurable skills. Despite all the hidden dangers connected to this paradigm, if high-quality education is accessible to people of any social class, hyper-meritocracy works.

“There is often this naive reaction a lot of people have” says Cowen. “They say, ‘Now I need to take X number of years off, learn all the skills of computer programming and become a programmer.’ Very often that’s a bad way to go. It’s people who integrate technical skills with knowledge of a concrete area and who understand marketing, presentation, and persuasion.”

Architecture is a field where innovation is very slow and, though architects have always seen change as an opportunity, it is demonstrated a skills gap within architecture around technology and digital aspects of design and construction. Quoting Cedric Price: “technology is the answer, but what was the question?”. What will be the lifeline for architecture allowing a redistribution of work and wealth? Technology is the answer: in terms of new skills and renewed competencies on techniques by which tomorrow’s architecture will be designed and constructed. From parametric design and AAD (algorithms-aided design), to automated manufacturing, to “big data” analytics and virtual/augmented reality, computation will be increasingly important as a tool in our environment (built and virtual). Architects should see computation as a technology leading to a crucial shift in industry and society and, more radically, one that can change the way they work. Far from the current individualistic tendency, a new profession could arise, based on the hyper-meritocracy paradigm extended to the large majority of design-professionals. Besides, roles that deal with relationships, negotiations, and active listening and these traits are among the most desirable skills for future professionals including: complex problem solving, critical thinking, creativity, people management, and coordinating with others.

A new profession arises

Algorithmic design is not simply the use of computer to design architecture and objects. Algorithms allow designers to overcome the limitations of traditional CAD software and 3D modelers, reaching a level of complexity and control which is beyond the human manual ability.

To face the unprecedented complexity of real world, designers must get a deep control and understanding of data-sets and, mostly, they have to find new strategies to collect data and process them in order to inform the design. From running-shoes to high-rise buildings or bridges, data are crucial to develop ambitious projects, which necessarily emerge as articulated entities, not as a representation of complexity but as the solution for complexity.

The current – and still evolving- stage of digitalization applied to architecture is demonstrating us that digital tools are useful to explore a potentially unlimited number of design solutions in order to find the best solution to a specific problem. The design project does not find his essence in a priori defined specific wills but it is the outcome of a process in which an important role is played by new forces that was impossible to describe and control so far. As Davide Lombardi says “the inspiration and guidelines of the design intent are no more collected from the rules of an architectonic tendency or from artistic influences but they found their reasons in sets of data gathered from the environment”. We not only refer to 1 to 1 scale built environment but primarily to the realm in which physical forces, structural strain and stresses or the molecular properties of materials exist and carry out their functions. Further, the environment is also the space in which huge masses of agents are spread out according with flock-based behaviour and responding to external stimuli defining new paths through cities and places. This enlarged environment has a strong multi-scalar future, from the microscopic to the urban scale.

It is possible to recognize the birth of new kind of professional – the computational designer -that deals with a wide range of computational tools that allow him to control and investigate the defined new environment. Data represent the real innovation introduced by the digital turn and embody the passing of representation as the main tool to design and show the project idea. Due to their neutrality and to the inner mathematical nature, the use of data within the computational setting has to be driven by mathematical rules. The data represent the input and the output of the design process, the start and the end point of an ideal path made by consecutive logic steps or instructions. This is the area in which the Algorithm-Aided Design is born. It explores new fields gaining is power from the ability to describe the complexity of the real world through numbers and mathematical functions. The AAD is funded on the analysis of the factors that affect the project and, when translated into data, it analyses and uses them in order to inform the process and to optimize the outcome according to a determined fitness function.

This tendency is also underlined by the always stricter relationship between architecture practices and academia. If one of the new fundamental prerequisites to survive on the market is to be highly skilled in a wide range of fields like logic thinking, data management and interpretation or coding (as well as the classical knowledge about how to imagine a concept or a space) it goes without saying that new practices have to activate interdisciplinary researches through the collaboration with universities or hiring people with cutting-edge backgrounds.

Therefore, in a kind of loop effect, this request of “architects 3.0” is also affecting the way in which architecture is taught and academic programmes are established and delivered. Following the example of well-known academic institutions spread across the Europe that have been ground-breaking in teaching architecture with a strong focus on digital tools and approaches, today all the school of architecture are pushing their students to be more and more engaged with digital devices that can help to carry out new projects and visions.

In this context also the profession of educator is going to change. New problems require new and different solutions that have to be investigated via innovative ways developed across the 4-5 years of an educational path. Teachers have to guide students to expand their ability to read and understand the world as a space full of information that have to be collected and ordered logically in order to generate, concurrently with sets of rules, a process. The main goal is to move away from the aesthetic-orientated approach to join a data-driven process that can lead the new architect to control all the phases of a design project, from the early design stage to the building site.

To sum up, the role of the architect is no more the one of the person with a strong creative attitude who draws the idea blowing up in his mind, but he is an expert in the use of logic strategies to explore all the aspects he wants to embed in his design strategy.

Arturo Tedeschi

with the contribution of Davide Lombardi

This text is an excerpt of the lecture hold at Architecture in Play – International conference – Lisbon 11th-12th July. Among the speakers: Michael Fox (President of ACADIA and director of Kinetic Design Group at MIT), Ruairi Glynn (Bartlett School of Architecture) and Paul Jackson (College of Art and Design in Tel Aviv).